![[Francis Naumann]](/4logo.gif)

Weilding a razor-sharpened pencil with surgical precision, midcentury American artist Gray Foy created a visionary body of drawings from 1941 to 1975—work then highly respected and collected by museums nationwide. Yet by the time of his death, in 2012, Foy’s reputation as an artist had faded. The discovery in his estate of a large cache of his drawings, most hidden away in drawers and closets, prompted a five-and-a-half-year research project aimed at reintroducing his work to the narrative of American art, an effort that culminates with this exhibition and the publication of a monograph commemorating his life and art.

Born in 1922 in Dallas, Foy spent his youth in Los Angeles. When he first painted seriously in the early 1940s—just after entering Los Angeles City College—his opaque watercolors and oils were patterned after such Surrealists as Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, and their predecessor Giorgio de Chirico. In compressed perspectives, stagelike scenes in deserted city- or landscapes evoke a sense of dislocation and menace.

![Untitled [Morphing Figures Inside a Tree-trunk Structure], ca. 1945](Foy - Untitled (Morphine Figures Insdie a Tree-Trunk Structure), ca. 1945.jpg)

![Untitled [Interior with Woman Standing at a Dresser], 1946](Foy - Untitled (Interior with Woman Stnding at a Dresser), 1946.jpg)

Untitled [Interior with Woman Standing at a Dresser], 1946

Untitled [Morphing Figures Inside a Tree-trunk Structure], ca. 1945

Beginning in 1943, Foy worked as a shipping expediter at the defense plant Lockheed Vega Aircraft in Burbank. Using standard-issue No. 2 pencils, he drew on procurement forms, depicting humanoid figures coincident with the carnage of WWII. Their malformed heads, torsos, and appendages emerge hideously from rocky outcroppings or the orderly domesticity of antique furniture. The moods of these drawings—trepidation about the present, a dwelling on transitional states, a confusion of internal and external biological systems, and an overriding awareness of mortality—persist through the later 1940s.

In the same period, Foy’s dexterity, style, and subject matter coalesced within the larger format of a spiral-bound drawing book, and the hallucinatory scenes that overflow its pages became his first cohesive visions. After atomic bombs were dropped on Japan, Foy responded by depicting human and animal inhabitants that reveal the instability of their molecular basis. Gravity loosens its hold, normal appendages transmute to amoeba-like extremities, and geometric symbols materialize overhead.

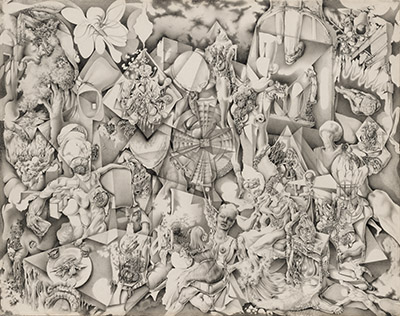

Foy soon departed from the drawing book format to make his largest drawing to date, Dimensions (ca. 1945–46). Disparate figures and body parts, interior furnishings, vegetation, and geometric shapes pulsate through a dense three-dimensional space that bleeds off the edges of the sheet. The spatial trickery rivals that of M. C. Escher.

Dimensions, ca. 1945-46

The Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Steve Martin

In Foy’s midcentury universe, when humans seek the comfort of familiar spaces they discover instead amorphousness, velocity, and weightlessness. The pictures also reflect an affinity with the work of American Realists such as Thomas Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry, whose tropes include the overlapping vignettes of mural painting populated by figures whose bodies are contoured to mimic their immediate setting. Foy goes further, as his characters are completely undone by their surroundings: a human leg transforms into that of a Queen Anne table, a face is flattened into a phonograph record, and the soles of feet replicate the shape of light bulbs.

Foy himself referred to his imagery as “super-realism,” and this direction was fostered when his wartime employment ended and he moved back to Dallas to renew his art studies, enrolling at Southern Methodist University beginning in spring of 1946. His art professors were leaders of the Lone Star Regionalist movement, and their work animated Foy’s impulse to explore the representational as a pathway to the allegorical.

In September 1946, on his first trip to New York, the twenty-four-year-old Foy took his portfolio to the influential art and literary publication View. View often covered the art of such Neo-Romantic artists as the Russian expatriate Pavel Tchelitchew. Each issue highlighted Surrealists, both European and American, and frequently a subset, deemed Magic Realists, that included such artists as Peter Blume and Paul Cadmus. Though Foy’s themes and style were generally aligned with Magic Realism, critics and curators often referred to his drawings as Surrealist. In the fall of 1946, View published Untitled [Courtyard with Morphing Figures], a seamless mix of the marvelous and the monstrous. Though unaccompanied by editorial comment or biographical information, its appearance launched Foy’s career.

Thus encouraged, Foy moved to New York in spring 1947, enrolling at Columbia University to study studio art and art history, as well as anatomy and botany, two fields that underpin much of his imagery. Soon, as in Tchelitchew’s work, Foy began his own explorations merging plant life with human features.

After asking for advice from curator Dorothy C. Miller at the Museum of Modern Art, Foy sought gallery representation, and R. Kirk Askew became his first and only dealer at Durlacher Bros. on 57th Street. Foy’s drawings were included in two group shows there and immediately began to receive notice. Reviewers noted the rigor of Foy’s scrutiny, describing his “microscopic vision” and “infinitesimal details glossed over by the average vision.” By the time of his first one-person exhibition at Durlacher’s in April 1951, Foy had nearly abandoned Surrealist imagery and began concentrating instead on the depiction of botanical organisms undergoing transitional states.

Though Foy had finally discovered his own voice, he did not have his second one-person exhibition at Durlacher’s until 1957. By then his observations of nature had radically matured, as evidenced by the complex biological invention in such works as Uprooted Plants (1955) and Grape Hyacinths and Fungi (1956). As his work evolved through the 1950s, the artist made clear his keen understanding of constant change in nature and honed his ability to depict such metamorphosis.

![Untitled [Fungi and Sprouting Botanical Forms], ca. 1970](Foy - Untitled (Fungi and Sprouting Botanical Forms), ca. 1970.jpg)

Untitled [Fungi and Sprouting Botanical Forms], ca. 1970

In the three decades Foy was active, he found a way to convey his fertile awareness of nature’s disorder as well as its order by continually refining his technical prowess and pushing the limits of detailing. Achieved by a delicate feathering technique, the edges of the depicted organic matter gradually disappear as lighter and lighter pencil pressure traverses the sheet. Form dissipates with the lightness of levitation, as if the furthest strokes of graphite still hover above the paper’s surface.

About 1957 Foy began a series of related still lifes in which his pictorial skills and command of imagery fused. Each drawing features one simple object in three-quarter view from a perspective that implies spontaneous discovery. The subjects involve leaves or branches wrapped by human hands into clusters or sheaves, or assembled by birds into nests. With its inner pinkish radiance and veined leaf surfaces, Cluster of Leaves (ca. 1957), for example, quivers with the power of an incubating egg. Metaphors for efforts to control the untamed sprawl of natural vegetation, these enclosures distill Foy’s insights and iconographic ingenuity.

In one group Foy developed an additional illustrative mechanism, preparing the drawing paper with a teeming texture, introducing earthy tones and chlorophyll-like colorations. The activated surfaces simulate soil incrustation, moldy walls, lichen-covered rocks, or pond scum. Foy invites the viewer to penetrate the dense and mysterious membranes of organic matter.

After receiving a career-affirming John Simon Guggenheim grant in 1961, Foy concentrated on his largest drawing, The Third Kingdom, in which subtle, monochromatic greenish-umber tones convey the prolonged activity of organic upheaval. Working on fibrous Japanese paper, Foy spent a year trying to illustrate elemental rock forms. What in full length might register as a distant mountainous landscape is in fact a meager patch of rock-strewn ground, whose surface articulation induces the feeling that the artist might yet delineate microbes.

The Third Kingdom, 1961-62

Such mature drawings focus on botanical and geological forms in the act of transformation, suggestive of the passage of time and the mutability of perception. They presage a modern-day concentration on ecological concerns by excavating the progression of natural processes. These humble, scrupulous compositions are the artist’s spirited attempts to render on paper the mysteries of the biomass and origins of the life force.

Like many others working in realist and Surrealist veins in the midcentury, Foy was subject to an American art world in flux and not particularly welcoming to his type of intimate imagist drawing. The grand narrative of modernism, then dominated by Abstract Expressionism and followed by a string of developments from Pop Art and Color Field to Minimalism and Conceptualism, tended to overwhelm work such as Foy’s in scale, concept, and direction. Without gallery representation and caught up in a fervid social life shared with his partner, Leo Lerman, Foy curtailed his production in the mid-1970s. Much of his inventory was dispersed with scant documentation. With selected works brought together for this exhibition and a major monograph further expanding awareness

of his oeuvre, Foy’s achievement emerges anew.

—Don Quaintance