![[Francis Naumann]](/4logo.gif)

![[Francis Naumann]](/4logo.gif)

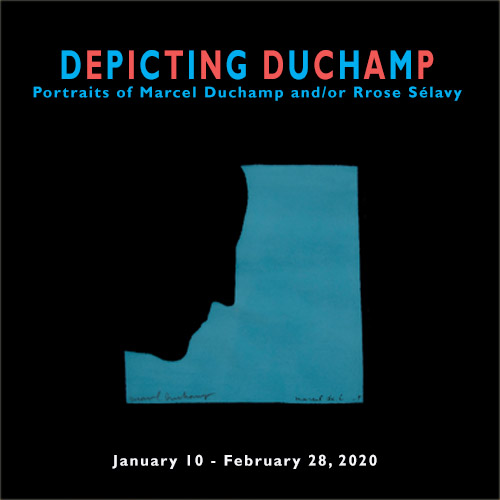

“Depicting Duchamp: Portraits of Marcel Duchamp and/or Rrose Sélavy” opens at Francis M. Naumann Fine Art on January 10, 2020. As the title suggests, the show will consist of portraits of Marcel Duchamp and/or the artist in the guise of his female alter-ego, Rrose Sélavy. Many were made in Duchamp’s lifetime, but countless portraits have been made of the artist in the years since his death. Indeed, a number were made by contemporary artists specially for inclusion in this show.

Marcel Duchamp’s reputation as an artistic iconoclast—combined with his legendary good

looks, genial character and accessibility—have made him the subject of countless portraits.

Indeed, if we combine the number of portraits made by his contemporaries with those made

posthumously, Duchamp has been depicted more often than any other major artist of the

modern era. Works of art are generally comprehended only visually (“retinal” in Duchamp’s terminology), and are, therefore, subject to evolving changes in taste. The ideas Duchamp introduced avoid fluctuations of style by inhabiting the mind, thereby forcing an intense and rigorous engagement with the process of thought. As a result, artists render him as a physical presence, for to this day, his ideas continue to affect the way we think about art and the art-making process.

The first formal painted portrait of Marcel Duchamp was made in 1915 by Walter Pach (1883-1959), an artist best remembered today for having helped to organize the Armory Show of 1913. It was Pach who had selected many of the modernist works in that landmark exhibition, including Duchamp’s infamous Nude Descending a Staircase. Consequently, he had done more to establish the artist’s reputation in the United States than any other single individual. In the painting, the artist wears a green shirt with a white collar and blue tie, and he is set against a modulated green backdrop that closely matches the color and texture of his shirt (green was Duchamp’s favorite color). Pach not only captured his sitter’s penetrating intelligence, but the delicate and attenuated features suggest an effeminate quality that the artist himself probably would not have denied, for with his invention of a female alter ego some years later, he would openly explore this aspect of his complex but ever-engaging personality.

The Pach portrait is the earliest dated work in the show, but it was followed by countless others made in the artist’s lifetime. Many photographs of Duchamp were taken over the years; see those by Denise Bellon (1938), Irving Penn (1948), Naomi Savage (1949), Victor Obsatz (1953), and Arnold Rosenberg (1958). He was depicted countless times by various painters, sculptors and printmakers, beginning with an early torso by his brother Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1910), plaster and bronze life casts by Ettore Salvatore (ca. 1945), sculptures by Reuben Nakian (1943), Isabelle Waldberg (1958), as well as to prints made by Man Ray (1971), Marcel Gromaire (1952), an etching by his sister Suzanne Duchamp (1953) and another by his eldest brother Jacques Villon (1956).

By and far the most ambitious series to depict the life of Marcel Duchamp was undertaken by the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris when they opened their inagural exhibition in 1977—eleven years after the artist’s death—with a Duchamp retrospective. To introduce this exhibition, they displayed a series of pictures illustrating the life of Marcel Duchamp painted by André Raffray (1925-2010), an artist who had earlier worked as an illustrator for the French cinema. Over a period of two years, he completed La Vie illustrée, twelve gouache panels that reconstruct major events in Duchamp’s life not otherwise recorded: from painting his first picture at age fifteen, to standing next to his Etant donnés in the last year of his life.

Curiously, the twelve panels in the series do not account for the eight years that Duchamp spent in New York from 1915 through 1923, arguably the most important and productive period of his life. The omission (likely a consequence of the Francophile nature of the enterprise), was rectified when Raffray was later commissioned by Francis M. Naumann to add a thirteenth panel to the series called Chez Arensberg (1984), depicting a typical soirée at the apartment of Louise and Walter Arensberg, Duchamp’s steadfast patrons during his years in New York.

Among the most engaging portraits of Duchamp are those done after his death, some by artists who are themselves today no longer living; see the works by Sarah Austin, Tom Chimes, Ray Johnson, Richard Hamilton. Yet it is the younger contemporary artists who give us the sense that Duchamp is still living, his ideas as prescient today as they were when first introduced over 100 years ago, forever altering the very definition of art; see Michael Vannoy Adams, Stefan Banz, Carl Bates, Larissa Bates, Ray Beldner, Nancy Becker, Mike Bidlo, Brice Brown, Rob Brinker, Pablo Echaurren, TR Ericsson, Robert Forman, Kathleen Gilje, Elise Graham, Tom Hackney, Rudolf Herz, Jasper Johns, Don Joint, Pamela Joseph, Larry Kagan, Jane Kaplowitz, L. Brandon Krall, Cary Leibowitz, Christa Maiwald, Carlo Maria Mariani, Sophie Matisse, Jacques Moitoret, Yasumasa Morimura, Richard Pettibone, Jonathan Santlofer, Donald Shambroom, Tom Shannon, Mark Tansey, Douglas Vogel, Ai Weiwei, CK Wilde, Rob Wynne and Tetsuya Yamada.

Reviews

New York Times, February 6, 2020