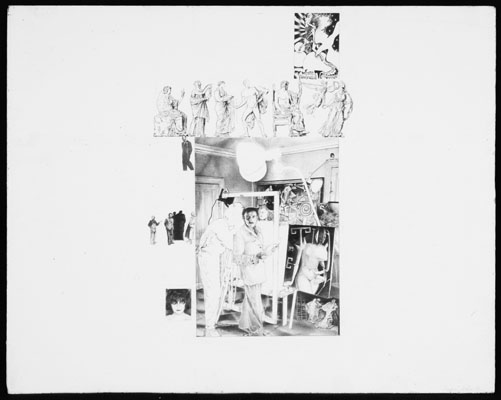

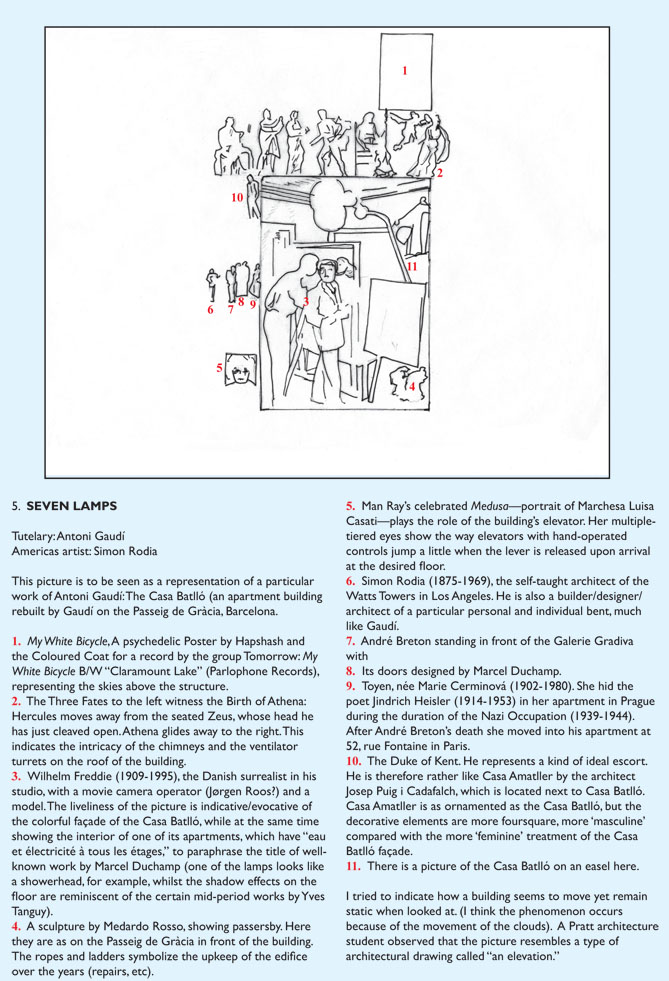

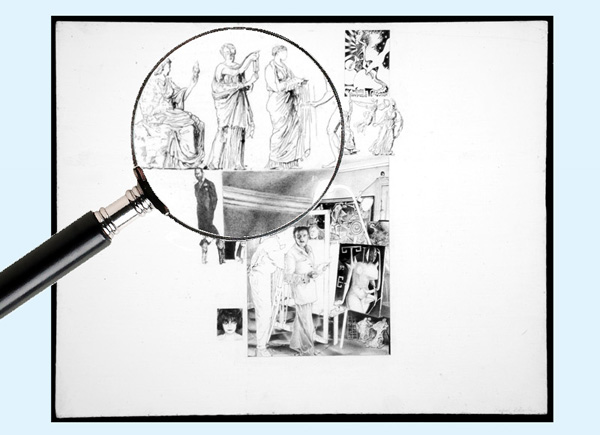

Extraordinary, remarkable, astonishing, phenomenal—these are words that inevitably come to mind when one views the work of Rafael Leonardo Black. The deftness and precision required to render such detailed imagery, not to mention the intellect and vast knowledge necessary for the construction of such complex narratives, is nothing short of awe-inspiring. To understand these works it is necessary to examine them in detail, but in some instances these details are so small and intricate as to require a magnifying glass and an accompanying diagram to fully fathom their inner workings. Even at this point, we need some sort of instructional guide to comprehend their overall message, for each element in the picture contributes to a theme that unifies its intent (sometimes disclosed by its title, which, in some cases, was selected years after the picture was completed).

In the interview that follows, Black reveals some of the artistic and literary sources that inspired his unique vision, from etchings by Picasso to the writings of the African-American writer Ishmael Reed. He singles out two essays written by the Italian metaphysical painter Giorgio de Chirico, articles in which De Chirico attempts to rekindle an interest in the work of the German symbolist painter and printmaker Max Klinger (1857-1920), and the Swiss painter Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901). According to De Chirico, these artists had fallen into relative obscurity due to a gross misunderstanding of their work. De Chirico felt that few actually perceived the classical underpinnings to their separate visions of the world, nurtured (no doubt to De Chirico’s delight) by extended residencies in Rome. Klinger’s work, he says, is “always based on a foundation of clear reality,” and he “often unites scenes of contemporary life and ancient visions in a single work, thereby achieving a highly effective dream reality.” Similarly, he tells us that “in Böcklin’s work the metaphysical power is always released by the exactness and clarity of a definite apparition.” He goes on to say that Böcklin gives us only the essence of what is necessary to convey a specific subject. “There is always little composition and very little embellishment,” he writes, “no more than is absolutely necessary to consolidate the preliminary vision during its ultimate elaboration. . . The more classical an artist is, the less evidence there is in his work of composition effort.” Everything that De Chirico writes of Klinger and Böcklin can be readily applied to the pictures of Rafael Leonardo Black, whose clarity of vision is self-evident, and whose complex and evocative narratives provide all that is necessary to explicate the story he wishes to convey, and nothing more.

John Dewey, in his book Art as Experience (1934), tells us that beauty can be perceived and honestly felt for precisely what it is, but if we want a more profound appreciation for a given work of art—what he called “an aesthetic experience”—we need to go deeper and make an effort to understand the work in all of its ramifications. Since the present exhibition and catalogue represent the first exposure of Black’s work before the public, every precaution has been taken to avoid the misunderstandings De Chirico felt befell the work of Klinger and Böcklin. All works in the show are reproduced and accompanied by detailed diagrams. These diagrams contain numbers in red that correspond to a list below that identifies each element of the composition. It is hoped that with this information at hand, the spectator can begin the journey of exploring the marvelous visions of Rafael Leonardo Black and, in the process, attain what Dewey described as a true aesthetic experience.