|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![[Francis Naumann]](../4logo.gif) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1877-1952) Katherine S. Dreier was one of the most tenacious and indomitable spirits to guide the course of modern art in America in the early years of the 20th Century. She was born into a family of wealthy German immigrants, who had encouraged their children to support various social causes, a conscientious approach to life that she brought with her to all artistic activities in which she engaged. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 1913, two of Dreier’s paintings were selected for inclusion in the Armory Show, the first major exhibition to introduce modern art to America. During trips abroad, Dreier had already seen examples of advanced European art, but it was the harsh reaction of conservative critics in New York that solidified her commitment to the new art; from that point onward, she would do everything in her power to promote its understanding and acceptance. In the fall of 1916, Dreier was invited to become a member of the Society of Independent Artists, a group of artists and patrons dedicated to staging annual, jury-free exhibitions of modern art. It was in their very first show in 1917 that Duchamp—under the pseudonym of R. Mutt—submitted his Fountain, a white porcelain urinal that was refused from display by an emergency meeting of the organization’s hanging committee. Dreier, who did not know Duchamp was the artist, voted against its inclusion, although she later sent a letter to him in which she attempted to explain her actions. “It is a rare combination to have originality of so high a grade as yours,” she wrote, “combined with such a strength of character and spiritual sensitiveness.” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

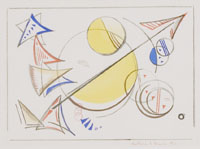

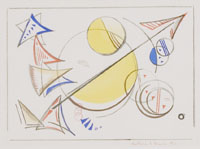

Variation 21, 1937

Black and white lithograph with pochoir coloring

9 3/8 x 12 ¾ inches |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

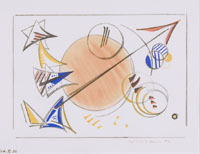

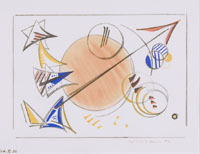

Variation 32, 1937

Black and white lithograph with pochoir coloring

10 ½ x 13 5/8 inches |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It is in comments such as these that Dreier best reveals the underlying motives for her attraction to Duchamp. For years she had been a firm believer in the teachings of the Theosophical Society, an organization founded in the late 19th century that professed the existence of a deeper spiritual reality, one that could be achieved only by those in possession of higher psychic states. Due in part to her heritage, she took a great interest in the teachings of Rudolf Steiner, founder of the German Theosophical Society, and she read the writings of Wassily Kandinsky, the great Russian abstractionist who had lived in Germany and who was himself an avowed theosophist. Elements derived from Steiner’s concept of “thought forms” combined with Kandinsky’s ideas about “hierarchic triangles” form the basis of Dreier’s Abstract Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, 1918 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), perhaps her most successful and dynamic picture from these years. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

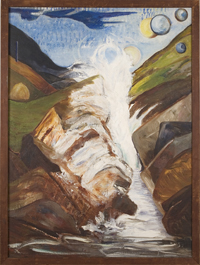

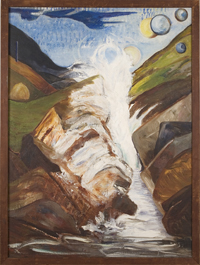

Waterfall, May 1931

Oil on canvas, 29 ¾ x 22 3/8 inches |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 1920, Dreier, Duchamp and Man Ray formed The Société Anonyme, Inc., the first museum of modern art in America. For the remaining years of her life, Dreier remained committed to this organization, presenting scores of exhibitions, educational programs, and a variety of publications. She avidly collected the work of artists who shared her commitment to modernism, eventually amassing a collection of over one thousand paintings, sculptures, drawings, photographs, and prints by artists from all over the world. Many of these artists were included in the International Exhibition of Modern Art, which Dreier organized for the Brooklyn Museum in 1926. Despite the work these activities required, Dreier never abandoned her artistic practice; in the 1930s she rented a studio on the Place Dauphine in Paris and, in 1937, she issued a series of lithographs called 40 Variations (each image individually colored by means of pochoir, a stencil-process overseen by Duchamp). It was her donation of the Collection of the Société Anonyme to Yale University and, after her death in 1953, the gift of her private collection to various American museums that marked the most significant and lasting achievement of her lifelong dedication to the world of modern art. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abstract Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, 1918

Oil on canvas, 18 x 32 inches

The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![[Francis Naumann]](../4logo.gif)